Why We Say Powell Street and Not “Japantown”

By Angela Marian May and Nicole Yakashiro

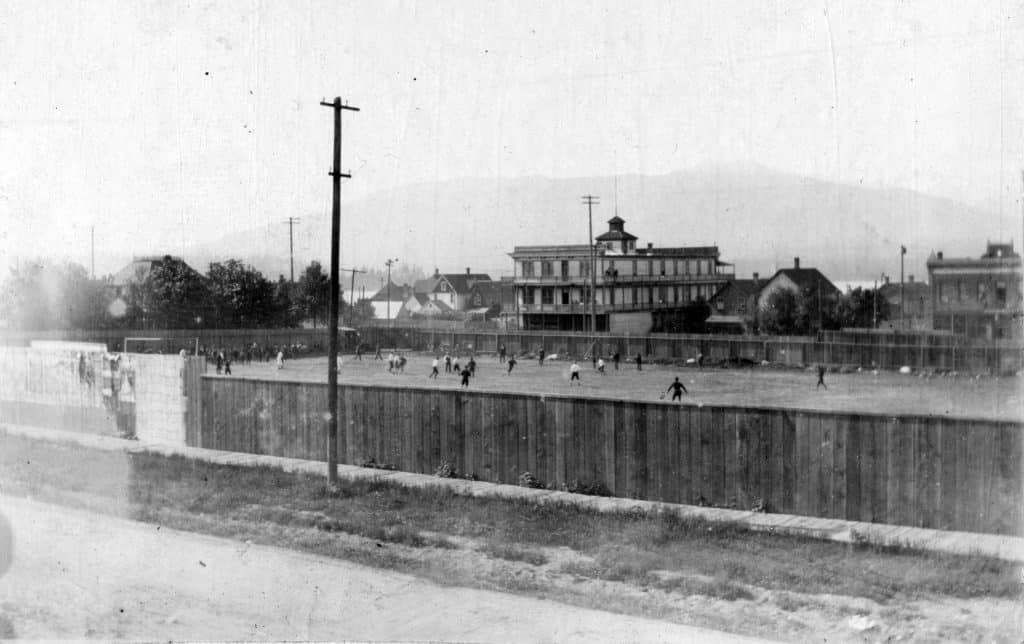

360 Riot Walk invites participants to trace a layered history of Vancouver’s labour politics, anti-Asian racism, and community resistance in what is today the Downtown Eastside. One of the Riot Walk’s key sites is the historic Powell Street neighbourhood, a target of rioters in 1907 and the former nucleus of the Japanese Canadian community before the federal government uprooted and dispossessed all people of Japanese descent in the 1940s. Talking and walking about these places may seem like nothing much at all, but the ways we do so matter. Even the names we give them shape how we understand a place’s history, its present, and its possible futures. This is why we say Powell Street and not “Japantown”.

Why do people keep saying “Japantown”?

The name “Japantown” has oddly garnered much traction in recent years. You can find it on Google Maps, in the City of Vancouver’s Heritage documents (though recent projects reflect a necessary change in terminology), and within newspaper articles. An easy-to-recognize moniker, the use of “Japantown” speaks to a wider history of ethnic and racial enclaves in Vancouver. Perhaps most well-known among these neighbourhoods is historic Chinatown, an area home to a vibrant Chinese Canadian community despite ongoing threats of gentrifying development. But at the same time that these urban spaces have been sites of community resilience, their creation was in large part a result of racist exclusion in Vancouver. The names given to these segregated places, including “Japantown,” marked the neighbourhoods as ‘foreign’ and outside the bounds of white settler society.

Over time, however, communities have reclaimed these names and employed them in new ways. Chinatown, for example, has become a name and place to mobilize around for many Chinese Canadian activists. But importantly, “Japantown” does not have the same history. It was never used widely among Japanese Canadians living on Powell Street before the Second World War. Instead, they more often used “Paueru-gai” (translating to “Powell town”), “Powell Street,” “Powell Grounds,” or “Paueru”. And the neighbourhood is simply no longer home to the Japanese Canadian community. This fact—a consequence of state removal—and the racist origins of the name makes calling the Powell Street neighbourhood, “Japantown,” a problem.

But why exactly is “Japantown” a problem?

To put it plainly, the name “Japantown” is a problem because it risks further displacement in the neighbourhood. While for some, calling Powell Street “Japantown” is a way to commemorate and claim the neighbourhood as a Japanese Canadian place, others—namely urban planners, policy-makers, and politicians at the City of Vancouver—have capitalized on this move to commemorate in order to gentrify the neighbourhood. If we take seriously the power of names and naming, we must reckon with the difficult fact that “Japantown” has been mobilized by the City in order to ‘revitalize,’ ‘clean up,’ and ‘beautify’ Powell Street at the expense of people now living in the area (see further reading below). This kind of ‘revitalization’ project is perverse because it recognizes the violence and injustice of the uprooting of Japanese Canadians, but in the same move—literally in the name of commemorating wrong-doing to Japanese Canadians—facilitates further violence and injustice by uprooting low-income, often Indigenous, racialized, disabled, and gender non-conforming people who now live in the neighbourhood.

The problem of “Japantown” is both straightforward and deeply complicated. Simply put, the name “Japantown” proposes a kind of Japanese Canadian commemoration that risks further violence in the neighbourhood: it commemorates Japanese Canadian presence by threatening to facilitate other people’s absence. At the same time, the issue is complicated. Looking to the nearby example of Chinatown, for instance, we might ask why “Japantown” is a problem but “Chinatown” isn’t. Looking to other examples of community-building and -organizing around names like “Japantown” across North America (overwhelmingly in the United States), we might ask why the name “Japantown” can’t work here. Yet the fact remains that in Vancouver, should we continue to use the name “Japantown,” we would be complicit in risking yet another iteration of violent displacement in the very place from which we were once forcibly removed.

But why does the problem of “Japantown” matter in the real world? For 360 Riot Walk?

At stake in this present-day displacement are the lives of people now dwelling in the Downtown Eastside. We, Japanese Canadians, were never the only people to live in this place. The neighbourhood has long been home to many people from all walks of life. To attend to the meanings inherent in 360 Riot Walk, then, and to think through, as artist Henry Tsang says, “who has the right to live here”—not just in the Downtown Eastside, but on unceded xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlil̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) lands—then we need to reckon with the fact that how we inhabit places, and the names that we give to places, are not benign. On the contrary, the ways that we take up and name space are meaningful decisions, products, acts—in a word, forces. They do things. Even as we advocate for the name of “Powell Street” or “Paueru-gai,” this name, too, is not perfect. Powell Street itself was named after Israel Wood Powell, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in British Columbia from 1872 to 1889, a fact which prompts us to further question the politics of names, naming, and commemoration in settler colonial Canada.

But the thing about names is that we can change them. We can adapt. In the meantime, we know that “Japantown” does things and that the things that it does are violent. As Japanese Canadians ourselves, along with others in our community, we refuse to let our history be weaponized against the Downtown Eastside. This is why, today, we say Powell Street and not “Japantown”.

Further reading (open access):

- Laura Ishiguro and Laura Madokoro, “White Supremacy, Political Violence, and Community: The Questions We Ask, from 1907 to 2017” from Active History, 7 September 2017, accessible here.

- Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre, “Revitalizing Japantown?: A Unifying Exploration of Human Rights, Branding, and Place,” exhibit publication, 2015, accessible here.

- Trevor Wideman and Jeffrey R. Masuda, “Toponymic Assemblages, Resistance, and the Politics of Planning in Vancouver, Canada,” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, vol. 36, no. 3, 2018, pp. 383-402, accessible here (with credit to the DTES Research Access Portal).

- Trevor Wideman and Jeffrey R. Masuda, “Assembling “Japantown”? A Critical Toponymy of Urban Dispossession in Vancouver, Canada,” Urban Geography, vol. 39, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-26, accessible here (with credit to the DTES Research Access Portal).

- Aaron Franks, Andy Mori, Ali Lohan, Jeff Masuda, and the Right to Remain Community Fair Team, “The Right to Remain: Reading and Resisting Dispossession in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside with Participatory Art-Making,” from feral feminisms, no. 4, 2015, accessible here.

- Trevor Wideman, (Re)assembling “Japantown”: A Critical Toponymy of Planning and Resistance in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, Master’s thesis, 2015, accessible here.

Further reading (behind a paywall):

- Jeffrey R. Masuda, Aaron Franks, Audrey Kobayashi, and Trevor Wideman, “After Dispossession: An Urban Rights Praxis of Remaining in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 38, no. 2, 2019, pp. 229-247, available upon request here.

- Kay Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown: Racial Discourse in Canada, 1875-1980 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995), see link.

About the authors

Nicole Yakashiro is a PhD candidate in the History Department at UBC studying settler colonialism in twentieth century British Columbia.

Angela May is a community activist, writer, and PhD student in English and Cultural Studies at McMaster University.

The ideas expressed in “Why We Say Powell Street and Not Japantown” originally emerged out of a research project called Revitalizing Japantown? (2010-2014), led by Drs. Jeff Masuda and Audrey Kobayashi (Queen’s University), to which Dr. Trevor Wideman (University of Toronto) was also a key contributor. Our articulation of these ideas here is made possible by their work. The article below is just one instance of what is now more than a decade of work to emphasize why we say Powell Street and not “Japantown,” and to resist gentrification in the Downtown Eastside.