Making of 360 Riot Walk

By Henry Tsang

360 Riot Walk was my first foray into 360 video technology, and although I had worked with video before and experienced various VR and AR projects, I soon learned that making something in surround-sight-and-sound required a significant shift in approach. In traditional filmmaking, the point-of-view can shift from third person (a fly-on-the-wall’s perspective) to first person (a protagonist’s perspective, say) to second person (someone responding to that protagonist). Camera movements such as tracking, dollying and zooming can be used to create a sense of moving through space or expose something revealing. Editing plays a key role in shifting perspective or location or time. Other formal devices that augment the power of editing are framing devices such as the wide, medium and close-up views. Controlling what, as well as, the way the viewer sees, is an indelible part of cinematic language and strategy. But in a 360 production, the viewer is in greater control of what they see. Editing is used more sparingly, for any change of location can be jarring, as if one’s entire body has been transported into a new space which requires a period of re-orientation, of settling in. Audio, which has often played a more supportive role to the visuals in cinema, moves to the foreground, as it becomes more influential. The viewer is now ever more so a listener, and the soundtrack has the power to direct them to relate and connect aural information with the visual world around them.

And interactive technology creates for the user an expectation that the information or stimuli provided, whether it be in text, visual, aural, or other sensorial form, be made accessible and if engaged with, that there should be a response or outcome. In the case of a walking tour, it was crucial that there be a reason to move from one location to the next, to stop here as opposed to just anywhere, and that there be something to learn or discover along the way.

In planning the tour, it became increasingly obvious that safety needed to be a priority. If the user were to walk along the tour route while looking at the screen of their mobile device, while listening to the soundtrack on headphones, their sight and hearing would be isolated, and their awareness of the surroundings would be seriously compromised. If someone were to cross a street in such a state of distraction (a phenomenon that has become commonplace ever since the introduction of the smartphone), they would literally be an accident waiting to happen. So we decided to restrict the interactive component to each of the tour stop locations. When the user arrives at a stop, they can take their time to orient themselves, find a safe spot to stand and spin around. Then they can start the next chapter by activating the gyroscope for motion response with the imagery and then starting the audio voiceover. When that ends, they are given verbal directions to the next location, supported by a map and compass on the virtual ground.

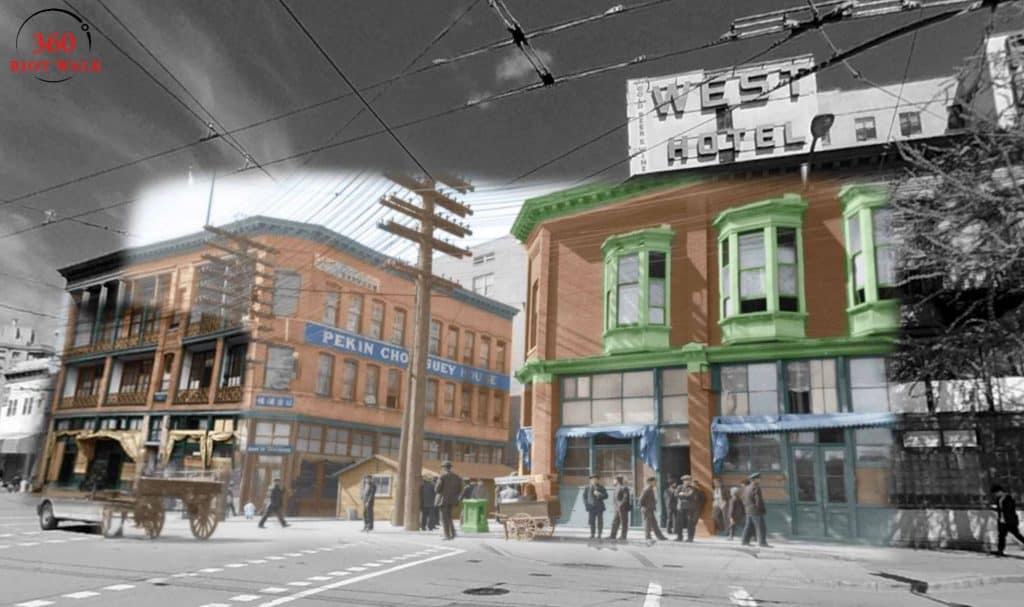

This approach greatly simplified the project, for we no longer needed to shoot video. Instead, 360 photographs were employed. In order to create a dissonance between the screen image and the surrounding urban landscape, the contemporary images of the thirteen tour locations were rendered into black-and-white, which is a genre associated with the past. In turn, the all black-and-white archival photographs and documents were colourized, in an attempt to make them more “real” – that is, relatable and appearing to reside in the same world of colour that we inhabit.

Embedding these historic documents into the 360 panoramas was a way to physically manifest, or conjure, the attitudes and representations of anti-Asian sentiment that was rampant, hyperbolic and often hysterical in the late 19th and early 20th century. American references were included to show that these sentiments were shared up and down the west coast, that kindred political and social forces were at play in many places, and that the white supremacist ideology embraced by those who controlled Vancouver at the time was common and normative.

The script was a collaboration between myself and Michael Barnholden, author of Reading the Riot Act: A Brief History of Riots in Vancouver, who had been giving riot walking tours for years. Since the publication of his book in 2005, more historical information had become accessible partly due to the digitization of archival materials, which we incorporated. We worked together on framing and articulating the theme of contextualizing the 1907 race riots within the history of white supremacy in Canada.

The script was given to Hayne Wai, former president of the Chinese Canadian Historical Society; Grace Eiko Thomson, curator, and Emiko Morita, executive director of Powell Street Festival for feedback. Their comments and suggestions were incorporated where possible, while navigating the challenge of maintaining a tight thematic focus and resisting the temptation to include more references and related stories.

The English script was then translated into the three other main languages spoken in the area in 1907: Cantonese (Catherine Chan), Japanese (Yurie Hoyoyon) and Punjabi (Masha Kaur). This was a whole project until itself, but significant. I wanted to include the linguistic and cultural backgrounds of those who were involved in this event. And importantly, I wanted to make this project accessible to recent immigrants who might not be aware of this historic event, and to reflect on what their lives might have been if they had come to this part of the world in a slightly earlier time.

A fifth language was also included: Squamish (Salia Joseph), which, along with hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, is one of the two indigenous languages of the area. It is present in the first stop of each of the four soundtracks, as it would have been at the time of early settler colonial contact. The presence of these languages is more than symbolic; they are functional, and they are a technology developed by people as a way to communicate with each other, to share experiences, with the potential to bridge differences.

360 Riot Walk was produced through the support of the Basically Good Media Lab at Emily Carr University of Art & Design where I teach. Sean Arden and Maria Lantin provided access to the 360 camera, software and editing equipment. They also gave invaluable advice and guidance for the production team of Arian Jacobs and Adiba Muzaffar, graduates of the Bachelors and Masters programs respectively, who shot the footage for the thirteen tour stops on a Insta360 One camera. Arian and Adiba also colourized and composited the over eighty archival photographs and documents into the 360 photographs they had taken. Pano2VR 360 editing software was used to create the navigation and interaction for the various visual and audio elements. I worked with the translators, recorded the voiceovers in the four languages, then edited the soundtracks. This was another new experience for me, for I had had almost no experience with audio and also didn’t understand Japanese, Punjabi nor much Cantonese (and still don’t). The translators were very generous and patient with me.

360 Riot Walk was launched on July 27, 2019 at the Sun Yat-Sen Chinese Classical Garden, which was a partner and host for project. Guided tours were given at the Powell Street Festival the following weekend, with more on September 7 and 8, the anniversary of the riots; these were at the Carnegie Community Centre and the Sun Yat-Sen Chinese Classical Garden.

In 2020, the 360 tour was significantly revised with upgraded visual elements, updated instructions in both text and video formats, and an actual website instead of just a bunch of 360 files sitting in a folder in a server. More research was conducted, more archival images were included, and every photograph, from the historic documents to the 360 photographs of each of the tour stops, was digitally enhanced, painstakingly re-colourized and re-composited. New graphics were created with a new logo, and new voiceovers were recording and edited. Efforts went into making the project more accessible, such as providing the scripts in the four languages, keyboard accessibility to navigate the tour without needing to use a mouse, creating instructional videos, and a video excerpt capturing some of the tour itself.

Also in 2020 was the rise of COVID-19 that affected the production workflow and plans for guided tours in the fall. And in some ways what was even more remarkable were the protests that erupted in the US, Canada and overseas following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and too many more black people for far too long a time. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and public awareness of systemic racisms across all sectors of society and particularly the dominant cultures, has created an environment that didn’t exist quite yet in 2019 when 360 Riot Walk was launched. It is my hope that this project joins with others in contributing towards the awareness and dialogue needed to build the change and create more agency for more people.