A Changing Chinatown: On Gentrification and Resilience

By Melody Ma, 馬勻雅

Next to the steaming windows of an Instagram-worthy cafe, young 20-somethings with beanies coddle their hot lattes. Down the street, a lineup snakes outside a streetwear shop for the latest sneaker drop. A DoorDash bike courier speeds past by, carrying the steaming vegan pizza he picked up from around the corner.

This is a scene that could be in just about any bustling North American city today. But the flaring red dragon lampposts, the looming century-old Chinese benevolent society buildings, and the waft of barbecue Chinese pork reminds us that we’re situated in Vancouver’s Chinatown — a gentrifying Chinatown.

Over a hundred years ago, Chinese labourers from six rural areas of a southern province of China, Guangdong, migrated to Canada’s west coast. In search of jobs and better wages, these men toiled away on the Canadian Pacific Railway, farms, and canneries.

Separated from their families, they slept in shifts in rooming houses above Canton Alley. Together, this early group of Chinese migrants created the dozen blocks we call Chinatown today. They set up shops, restaurants, and societies to support each other despite being away from their kin.

However, the presence of Chinese migrants was not welcomed by everyone. In 1885, the federal government introduced a Chinese Head Tax aimed to halt Chinese immigration. The Chinese Immigration Act was passed less than twenty years later, further limiting the possibility of any family reunification. Despite the racist state-directed efforts to eradicate the Chinese community, they remained steadfast and resilient in Chinatown. The presence of the neighbourhood to this day is a mark of the community’s strength.

Today, Chinatown faces a new threat: gentrification. Gentrification is a powerful displacing force creating crisis in the communities we live in. It is a process of class displacement where an influx of wealthy people displaces the existing poor.

The trail signs of gentrification are familiar: Cafes are a little fancier. A new grocer selling $9 juice moves in. The faces on the street start to look different. Rent hikes upwards. The sights, smells, and sounds of the neighbourhood changes. Existing residents find themselves excluded from places where their old haunts used to be. Slowly but surely, an unfamiliar neighbourhood emerges.

Though Chinatown is recognized as a National Historic Site of Canada, the neighbourhood has been squeezed under the intense pressure of gentrification over the last decades along with the rest of the Downtown Eastside. Layered on top of class displacement, Chinatown faces another unique threat — gentrification is also actively eroding Chinatown’s distinct cultural heritage and history.

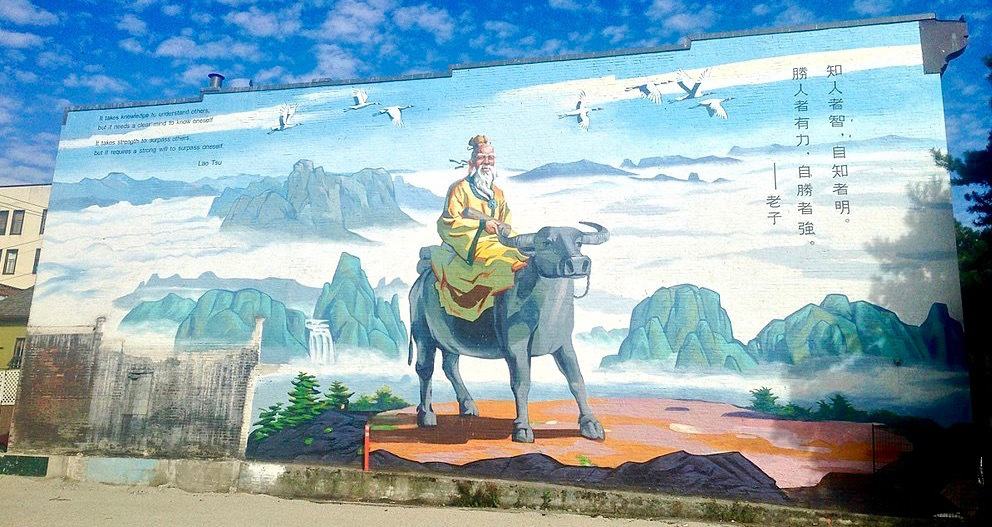

Take for example, the fate of the magnificent floor-to-ceiling mural of Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu on an ox painted on the side of the 100-year-old Lee Society Building. Now in its place stands a bright gold microsuite condo tower boasting a cold-pressed juice and coffee lounge on the ground floor. A budget-friendly Hong Kong cafe on Main Street was supplanted by a hip pizza shop. Affordable, culturally-appropriate green-grocers lining Gore Avenue are replaced by aesthetic millennial boxing gyms that cater to the gentry, resulting in the loss of valuable cultural food assets.

The combination of economic and cultural displacement through building new housing and amenities catered to a new and wealthier demographic creates “zones of exclusion”. Earlier residents are no longer welcomed in their own home. Gentrification and cultural erasure are the new anti-Asian riots and Head Tax, and they are just as violent and exclusionary.

But the Chinatown community is not known to sit on the sidelines. Repeatedly through history, the community rose up and pushed back against the forces that sought to eliminate its place.

In the 50’s through 60’s, moving cars efficiently in North America was all the rage. This urban planning philosophy was coined “urban renewal”, which encouraged cities to build freeways to revitalize so-called “blighted” neighbourhoods. In Vancouver, urban renewal led the way to a proposal for a freeway to be constructed through Chinatown and the surrounding Strathcona neighbourhood in the late 60’s. The Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association (SPOTA) fought vehemently against the destruction of their home and thankfully succeeded. Their tenacity helped save Chinatown.

Decades later in 2017, multiple generations banded together to push back against a shiny new condo tower proposed for 105 Keefer, a site that’s situated right next to a memorial for the Chinese laborers who built the railroad. The multigenerational activism led to the eventual government rejection of the condo project.

Both the freeway and 105 Keefer fights were watershed moments for Chinatown. They demonstrated there was a fighting chance the neighbourhood could be saved by the same resilient spirit of our forefathers who also fought for their survival more than a century ago.

The story of Chinatown isn’t finished as I write this in 2021. The global pandemic has created an onslaught of new challenges for the neighbourhood. The same racist sentiment toward Chinese people and Chinatown are replayed again and again like a broken record.

Will the neighbourhood finally succumb to the pressures this time, or will community resilience prevail as it always has? Let’s hope it’s the latter.

About the author

Melody Ma 馬勻雅 is a Chinese Canadian who led the #SaveChinatownYVR campaign.